During my research days at Hertfordshire Business School, I analysed Tarbes S.A., its transitional journey, the strategic management demonstrated between 2010 and 2015, the executive challenges encountered, and its use of strategic business tools, including Porter’s Five Forces, SWOT and PESTLE.

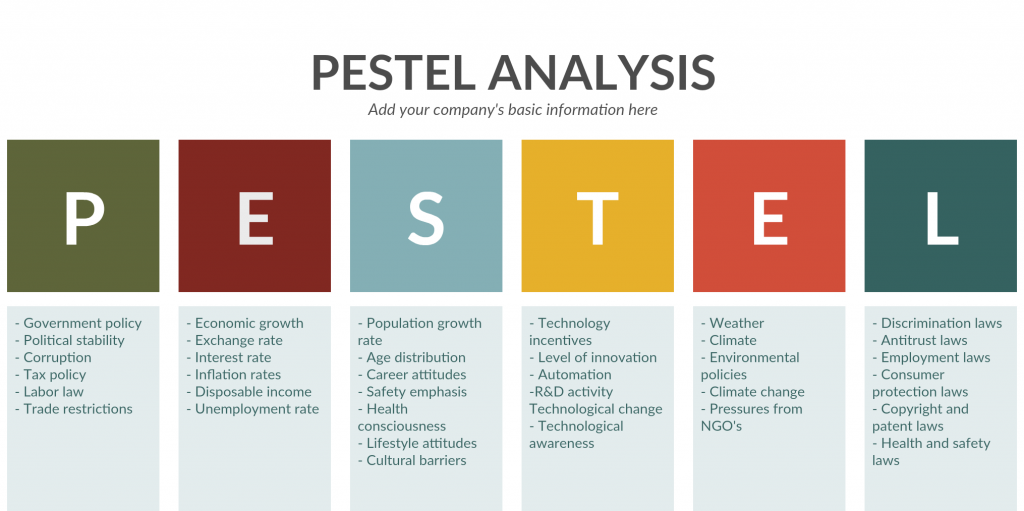

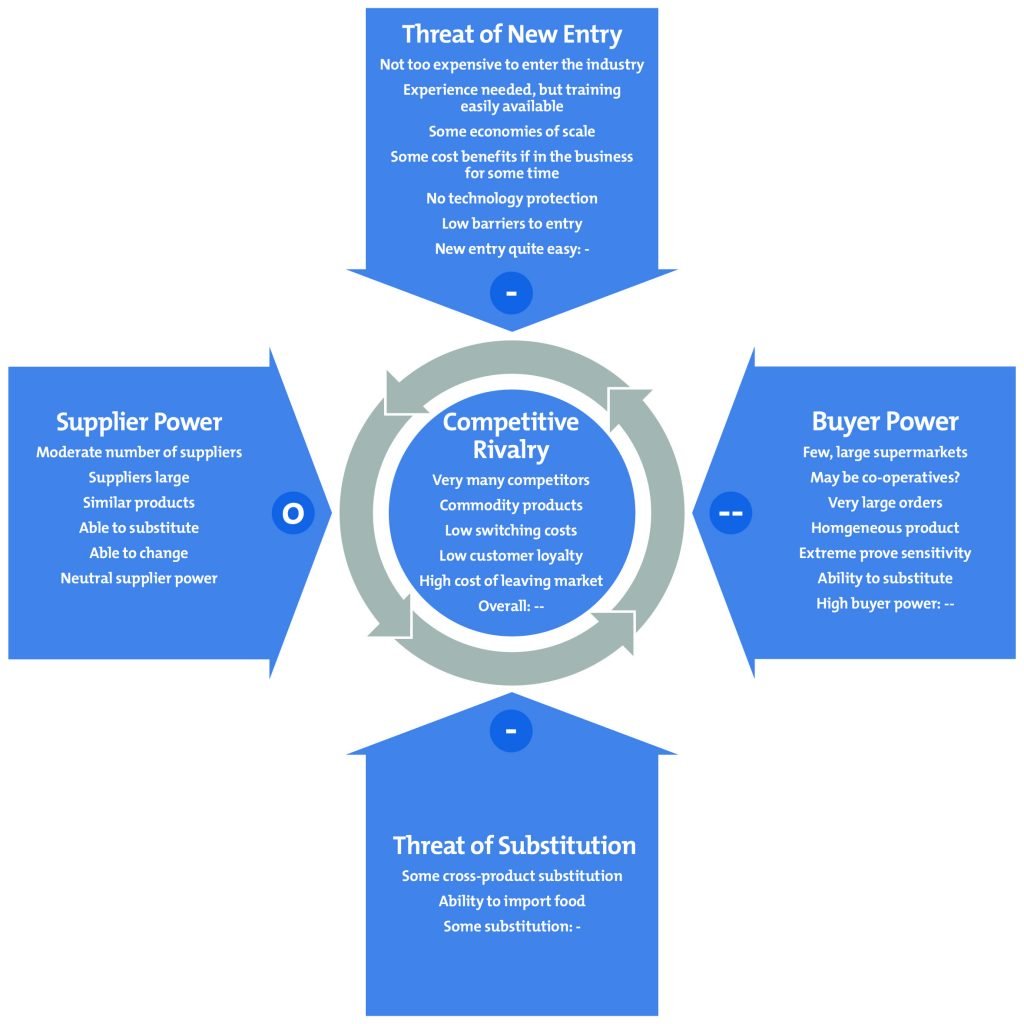

I kept the reflection section offline; please reach out if you have any questions; the same applies to annexe 1 (PESTLE analysis), annexe 2 (Porter’s 5 Forces analysis) and annexe 3 (SWOT analysis).

Strategic management at Tarbes S.A. – Giant Carousel – driven by Yara Branco

Based on ‘Turning around a national icon: Yara Branco at Tarbes S.A’ (Ken Mark, 2012)

Introduction

The following paper analyses the strategic issues encountered by Tarbes S.A. (“Tarbes”) between 2010 and 2015 by applying a variety of tools such as Porter’s Five Forces (1985), PESTLE and SWOT analysis and by interpreting the findings using theoretical concepts and appropriate strategic paradoxes applicable to the business.

Tarbes was South America’s largest manufacturer of computer tablets when a series of events challenged the company’s leadership position. Yara Branco took the leadership of the company in January 2010 after several assignments in which she proved to be able to turn around poor-performing companies by having a straightforward, practical approach to business processes, emphasising teamwork, social and soft skills and making decisions based on input collated from all members of the team.

Localisation vs globalisation paradox

Tarbes’ well-established domestic performance is described throughout the paper, starting from the first paragraphs, where the business is characterised as South America’s largest manufacturer of tablet computers.

The study case claims that the business has accumulated a top three share in all significant urban national markets and later expanded to Peru and Argentina, the second most prominent countries in South America, aiming to optimise the distribution network coverage substantially.

Scope

Despite the expansion to Argentina and Peru, based on Patel and Pavvit’s (1991) definition of international expansion, it can be assumed that Tarbes does not particularly seek to expand globally and that its only objective was to improve its distribution network within South America.

Porter’s Five Forces (1985) analysis outlines several characteristics which Tarbes emphasises, including the national distribution chain formed of 1850 distribution points and the awareness captured through the local and national newspapers, without having references to the international space.

Expansion

Tarbes’s expansion to Peru and Argentina aimed to sell the same product produced in Brazil in neighbouring countries. This behaviour is described by Levitt (1983) as a worldwide similarity, and given the area covered, it can be argued that the expansion is at its initial stages. Despite matching Levitt’s (1983) profile internationally, a SWOT analysis of the firm confirms that it has set a broad spectrum of objectives, including redesigning the products, researching improving the user experience levels and addressing operating system issues. Therefore, the company’s expansion to the international markets is not receiving substantial attention.

International software markets

Tarbes delivers tablets with a particular operating system. The company wants to expand the market by allowing third-party developers to create compatible apps. Tarbes has assigned 30 software engineers to help with this expansion. However, reports indicate that competitive brands using Windows and Android operating systems have 2,000 software developers for their marketplace, much more than Tarbes.

This raises questions about the company’s ability to expand while supporting the app market’s growth. Management of custom software development in international markets could help the company’s reputation.

In 2009, the brand introduced two product variations for industrial use, with longer battery life and more robust case. Prahalad and Doz (1987) and Bartlett and Ghoshal (1987) recommend launching only one product from a broader portfolio in the global market. In this case, Tarbes tablets could offer industrial variations. Adopting partial globalisation also involves accessing shared services like customer support, warranties, and returns if strategic management principles are followed.

Partial internationalisation

However, partial internationalisation for a niche industry is only a simple strategic option; it will introduce dependency services, which Tarbes may need access. Partial globalisation applied to a niche market also requires research to compare and contrast local products from the targeted foreign markets, which may compete with Tarbes. Evidence of such, as research is not presented within the study case, means Tarbes would not be prepared for partial globalisation of their hardware variations.

Globalised economies and strategic management

Dunning (1986) and Kogut (1993) discuss how companies in the technology sector expand into foreign markets. They need to determine whether managers can effectively use strategic management to control whether the business stays local or goes global.

These theories suggest that companies often follow less regulated expansion plans. This aligns with Tarbes’ PESTLE analysis of how they entered the Argentinian and Peruvian markets. According to Kogut (1993), the company expanded into other countries, like Brazil, due to natural evolution.

This idea is supported by Porter’s Five Forces analysis, which shows that the company had a strong presence. This situation almost forced the company to expand into neighbouring countries.

Product design and production

Despite expanding outside Brazil’s borders, no external influences are imported into the product design and production. The management delivers from within Brazil, and it can be argued that the expansion occurred due to the prominent market share already secured in their home country.

This led to a natural increase beyond Brazil’s borders, which was reactive instead of strategic action and took place for distribution purposes (Porter, 1985). In light of the globalisation and localisation paradox, Tarbes is inclined towards the latter element, with little strategic appetite for globalisation.

Market vs resources

Conflicting demands of market adaptation generate the Market and Resources paradox in conjunction with resource leveraging. The paradox presents a misalignment between the market needs and the resource base, including the value chain within a business.

Industry dynamics and resource alignment

Whether Tarbes developed resources that fit the environment and industry dynamics is complex. Although the PESTLE analysis highlighted a substantial number of engineers involved in critical business processes, i.e. production, design and sales, it is known that the running software has raised concerns and requires updating.

Also, the existing tablets running Microsoft and Android operating systems capture the interest of users who seek to develop bespoke software on these platforms. This process is aided by open-source communities assisting the 2,000 engineers employed by companies such as Toshiba and IBM.

Strategic management as a tool

Tarbes has only 30 engineers supporting its software development community. This shows that the company needed to build learning organisations, understand industry trends, and adapt its resources to industry changes. It may have gained financial advantages, increasing its popularity.

However, letting users interact with the platform using custom software is essential. The interest in the iPad product demonstrates this, with 70% of people aware of its launch likely to buy it.

Spatial separation

A parallel processing method has been developed to avoid confusing market dynamics with resources and value chain processes. Different business functions handle various activities, allowing senior leaders to strategise based on lower-level reports. Tarbes has a top-down structure with a central management team of six overseeing four business units managed by an executive director and five operational directors.

None of the four business units (Development, Production, Sales, and Marketing) specialises exclusively in resource leveraging and value chain management. This suggests that Tarbes may not effectively use spatial separation as a strategic tool.

Dynamic capabilities in strategic management

In contrast to Special separation, strategising managers can opt for the Dynamic capabilities technique and juxtapose the demand for resource leveraging and the need for market adaptation (Teece et al., 1997) through a continuous regular contrasting process. Managing the Market vs Resources paradox using the dynamic capabilities framework can be done at any level, such as project, programme, unit or organisation.

Blue ocean vs red ocean

A similar principle strategy managers apply lies within the Blue Ocean vs Red Ocean (Kim & Mauborgne, 2005) paradox, where the organisation turns on or off the market boundaries and industry structures whilst delivering a service.

The argument behind the Red Ocean is that companies have their service in a framework dictated by the industry, that there needs to be more innovation embedded, or that none or minimal elements emerge from the service delivery to the market and are outside the market norm.

To sustain themselves, businesses operating under the Red Ocean model rely mainly on operational efficiencies to gain a competitive advantage instead of through strategic differentiation, as Porter (1985) recommends.

Strategic management and innovation

Following the Blue Ocean model, organisations must perceive pre-set market boundaries or industry structures.

Blue Ocean, such as Uber or Airbnb, always strive to reconsider the industry boundaries from actions and gestures made by key industry players, effectively updating their model agilely to suit changes in the ecosystem and gaining competitive advantage from strategic repositioning movements.

Tarbes appears to be aligned with the Red Ocean model; however, in early 2010, Branco gave strong signals suggesting that substantial business changes are required following Hammer’s (1990) recommendation “Reengineering work: do not automate, obliterate”.

Stuff turnover

Tarbes does not refer to any suitable integration to manage the Market vs Resources paradox. However, the Porter analysis suggests the organisation was inclined predominantly towards the resource leverage of the contradiction through the emphasis on the low staff turnover, the staff requirements and the feedback provided by the staff members.

The downfall of not counterbalancing the industry dynamics with resource adaptation is reflected in the loss of market share, even before the iPod launch and secondarily through a variety of smaller factors such as the failure to deliver qualitative software and the market space limitations. Despite the above, there is yet to be a mechanism to confirm if the requirements for the resource leverage are suitable for the existing market conditions and would suit the business needs to accelerate the company’s competitiveness.

Revolution vs evolution paradox

The Revolution and Evolution paradox talks about the distinction between disruptive (Grinyer et al., 1987) and gradual change (Quinn, 1980) taking place within organisations (Greiner, 1972; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996). It refers to the ability of members to adapt to changes and the impact these changes may have on the team’s ability to change. This paradox claims that radical integration of change can be done either (Strebel, 1994) through disruptive (Baden-Fuller & Stopford, 1992) or gradual (Johnson, 1987) change.

Cultural resistance and strategic management

Tarbes made a few changes before Yara Branco arrived. Top management drove these changes. Branco received communications that showed resistance to change, both psychologically (as described by Argyris in 1990) and culturally (as noted by Tushman et al. in 1986). This resistance was evident because people kept emphasising the existing practices and mechanisms in the business.

There is no proof of investment lock-in resistance to change (as mentioned by Ghemawat in 1991). This is because the company had to commit financially to a 5-year project. However, there is some evidence of political resistance to change (per Kruger in 1996). This is because the current operating system is a Linux-based proprietary software, and efforts, assets, and values have been invested. Some people might be hesitant to accept a change in the operating system.

Strategic management and business agility

From a technical perspective, the argument is more assertive. Shapiro and Varian (1998) state that lock-in creates a strong dependency on software embedded in Tarbes’ products. The SWOT analysis highlights Tarbes’ market leadership position.

The report confirms that out of 6,000 staff members, 3,500 are engineers. Leveraging their expertise may have contributed to Tarbes’ market leadership in Brazil. This may result in a competence lock-in effect (as described by Leonard-Barton in 1995), where many in the business are unwilling to accept change.

Strategic management perspectives on change

The analysis reveals that there are factors within Tarbes that resist change. However, if the strategic change is imposed in a radical (following Stinchcombe’s 1965 approach) or revolutionary (as suggested by Gersick in 1991) manner, the company’s staff can realign with the new order. The SWOT analysis indicates that the need for change has been recognised and is now on Branco’s action list.

Exploration vs exploitation paradox

The Exploration vs Exploitation paradox applies to environments where change is required. It becomes an exercise to assess if the change should be driven by improving the internal existing structure or externally through new disruptive processes or technologies (Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996). Although exploitative and explorative methods are required, generating them requires different approaches. Exploitation uses the current techniques to improve the results, which requires input from employees, consumers or stakeholders.

Temperature check

This can be done through questionnaire forms or interviews and would constitute a relatively soft change within the existing practices, aiming to improve performance. However, the business defines that. The explorative side involves a new technological idea brought into the organisation, implementing it and then leaving the staff to accommodate.

Strategic management at Tarbes

Before the arrival of Branco under the leadership of Tarbes, the analysis frameworks gave evidence of soft exploitation attempts of a reactive type, such as the initiative to address the issues caused by the operating system. Branco does claim to have identified and prioritised that the firm needs to lean towards the exploration side.

Parallel processing

Exploration and exploitation require different mindsets and cognitive skills, so it would be challenging to implement both simultaneously (March 1991). However, by focusing both processes on other business functions and rotating periodically, the organisation will benefit from implementing exploitation and exploration (Christensen, 2011). This permutation is called parallel processing, and organisations that use this are called ambidextrous organisations (Benner & Tushman, 2003).

Tarbes could internally approach parallel processing (Tushman & O’Reilly, 2004) by opening an R&D internal function. The risk in driving parallel processing is a need for more visibility from the R&D function of how future host functions operate.

Power delegation

Alternatively, Tarbes could drive change from the outside. Branco may need to delegate power to an outside business partner despite being hands-on and direct. In both cases, the exploitation can be managed in-house and entails identifying and generating operational efficiencies and training staff to utilise the new technologies.

Balancing strategic management priorities

Tarbes could achieve the Balancing system with the exploration and exploitation paradox at the organisational level. However, research shows that moving from one stage to another at the company level may be more complex than parallel processing (Smith & Tushman, 2005).

Tarbes could achieve the Balancing system with the exploration and exploitation paradox at the organisational level. However, research shows that moving from one stage to another at the company level may be more complex than parallel processing (Smith & Tushman, 2005).

Tarbes should utilise the Balancing or Parallel processing technique as long as the change is integrated within the business and cyclical or phase-based. Branco must do so to maintain the loss of market share and trust and establish a safe stance concerning Apple’s new product.

Conclusion

Tarbes had followed a narrow view with a direction which pushed the giant away from the market trends. The leadership position reached a peak point where it became less sustainable to support the market share two-thirds claim. Luckily, Branco has identified the fundamental weaknesses.

According to the paradoxes identified above, the strategic challenges may be addressed through prompt and effective implementations across the company, mainly from realignments or the adaptation to the industry needs and dynamics.

References

Benner, M. (2002). Dynamic or static capabilities? Process management and adaptation to technological change, Working paper, The Wharton School, University of University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Benner, M., & Tushman, M. (2002). Process management and technological innovation: A longitudinal study of the photography and paint industries, Working paper, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Christensen C. M. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business Press.

Dunning, J. (1992). “Multinational Enterprise and the Globalisation of Innovatory Capacity” in O. Granstrand et al., Op. Cit.

Gersick, C. J. G. (1991). Revolutionary change theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 10.

Patel, P. and Vega, M. (1997). “Patterns of Internationalisation of Corporate Technology: Location versus Home Country Advantages”, submitted to Research Policy.

Porter, M. E. (2008). The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy, Harvard Business Review.

Quinn, J. B. (1980). Strategies for Change: Logical incrementalism, Richard D. Irwin, Homewood, Illinois.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management, Strategic Management Journal, 18 (7), 509-533.

Tushman, M. L. & O’Reilly, C. A. (2002). Winning through innovation: A practical guide to leading organisational change and renewal. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tushman, M. L. & Elaine Romanelli (1985). “Organisational Evolution: A Metamorphosis Model of Convergence and Reorientation,” In Cummings, L. L. and Barry M. Staw (Eds.), Research in Organisational Behavior. Vol. 7, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, pp. 171–222.

Other references

Argyris, C. (1990). “Overcoming Organisational Defences: Prentice Hall”.

Baden-Fuller, C., Stopford, J.M. (1992). Rejuvenating The Mature Business London: Routledge.

Bartlett, C. & Ghoshal, S. (1989). “Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press” Behaviour and Organisation, pp. 9, 5–24.

Ghemawat, P. (1991). Commitment: The Dynamics of Strategy. Free Press, New York.

Greiner, L. E. (1998) Evolution and revolution as organisations grow. Harvard Business Review, 76, 3, 55-68.

Grinyer, P. H., Mayes, D. G. & McKiernan, P. (1988). Sharpbenders Oxford: Blackwell Gronroos, C. (1994) From Marketing Mix to Relationship Marketing: Towards a Paradigm Shift in Marketing Management Decision, 32 (2) pp 4–20.

Johnson, M. (1987). The body in the mind: Bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1987.

Ken Mark (2012). ‘Turning around a national icon: Yara Branco at Tarbes S.A’, in Bob de Wit and Ron Meyer (ed.) Strategy and International Perspective. India: Cengage Learning India Private, pp. 685.

Kim, W. C. and Mauborgne, R. 2005, Blue Ocean Strategy. Harvard Business School Press.

Kogut, B. (1985). “Designing Global Strategies – Comparative and Competitive Value-Added Chains”, Sloan Management Review, 26 (4): 15–28.

Krüger, W. (1996). “Implementation: The Core Task of Change Management”, CEMS Business Review, 1, pp. 77–96.

Other references

Leonard-Barton, D. (1995). Wellsprings of Knowledge: Building and Sustaining the Sources of Innovation, Boston, MA, Harvard Business School Press.

Levitt, T. “The Globalisation of Markets,” Harvard Business Review, 61(3), May-June 1983, pp. 92–102.

March, J. G. (1988) “Variable Risk Preferences and Adaptive Aspirations” Journal of Economics.

Marketing News, “Standardisation not Standard for Global Marketers,” September 27, 1985a, pp. 3-4.

Shapiro, C. & Varian, H.R. (1998). Information Rules, Harvard Business School Press, http://www.inforules.com.

Shuen, A. (1994). “Technology sourcing and learning strategies in the semiconductor industry”, unpublished Ph. D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Smith, W. K., & Tushman, M. L. (2005). Managing Strategic Contradictions: A Top Management Model for Managing Innovation Streams. Organisation Science, 16(5), 522–536.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). Organisations and Social Structure. In: March J editor editors, Handbook of Organisations, Chicago: Rand McNally, pp. 153–193.

Strebel, P. (1994). “Choosing the right change path”, California Management Review, 36 (2), pp. 29–51.

Yves, D., Bartlett, C. & Prahalad, C. K. (1981). “Global Competitive Pressures vs. Host Country Demands: Managing Tensions in Multinational Corporations”, California Management Review 23 (3): 63–74.

Yves, D., Santos, J. & Williamson, P. (2002). “From Global to Metanational: How Companies Win in the Knowledge Economy”, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.